‘Second Class Bath’

The social life of water and washing provides a way to understand the history of cities. In Liverpool in the midst of a cholera epidemic in 1832, Kitty Wilkinson, an Irish immigrant, offered her own house and yard to wash her neighbours’ clothes. Kitty, who became known as the ‘saint of the slums,’ used chloride lime (bleach) to rid the rags of disease for a penny. Clean water and washing was a way to combat the spread of lethal disease in cities. Ten years later the first warm fresh-water public wash house was opened on Frederick Street, Liverpool.

‘Wash house Laundry’

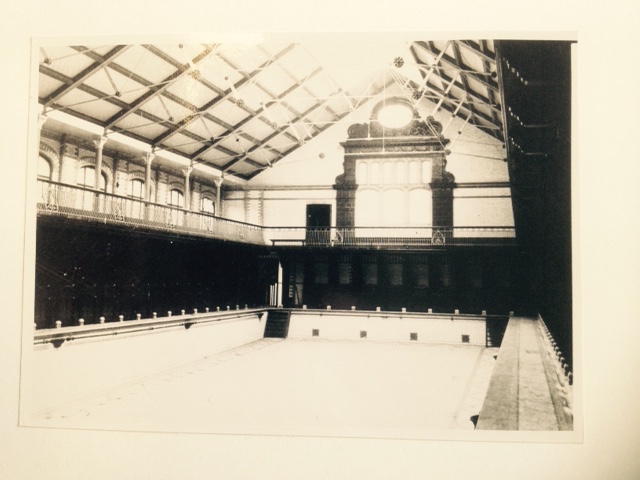

It couldn’t be more appropriate that for the Centre for Urban And Community Research to be housed in a former washhouse and swimming pool in Laurie Grove, New Cross. The washhouse was a tool for social improvement, a place for the industrial poor to get clean. In the winter the pool was covered with boards and converted into a dance hall and provided a place for racial integration in a period when an intense colour bar was enforced in the local pubs and other leisure spaces.

Thousands of south Londoners learned to swim here. It was a place where childhood memories were made. The pools were closed in 1991. In 1994 the building became the home of the CUCR, part of Goldsmiths College, and an international renowned research centre on city life. It couldn’t be a more perfect context to conduct urban studies, for the building itself is like a microcosm of the social history of the area.

Laurie Grove Baths

The baths opened on April 20th 1898, as part of a municipal drive to improve the plight of the ‘great unwashed ‘ of industrial south London. Architect Thomas Dinwiddy designed it costing £48,695, he also built local hospitals, schools and workhouses. The impetus to build public baths and wash houses was primarily a bid to improve social conditions amongst the labouring poor. The construction of Laurie Grove was authorised under the Public Baths and Wash-houses Act of 1846, which allowed borough councils to raise funds for social improvement through hygiene and cleanliness. And people welcomed these developments.

The Laurie Grove building consisted of three swimming pools; Large, Small and “South pool” which was completely separate, accessed from the main building by underground passages. It also included baths for washing and getting clean but this was a profoundly segregated social affair. There were separate baths not only for men and women but also “1st and 2nd Class” bathers. At the rear of the building was a laundry for washing and drying the bath-towels. The Deptford Official Borough guide of 1910 announced that “a large laundry containing accommodation for 35 washers, of whom there nearly 10,000 in a single year.”Laurie Grove was designed to be at the centre of all the other “wash houses” in S.E London including Clyde Street, Forest Hill, Bellingham and Downham. The cost of using the laundry in 1936 was one and a halfpennies per-hour inclusive.

‘First Class Baths’

Getting clean at the washhouse could be last form of dignity left to those who had fallen into destitution. Peter Powers grew up in the baths, his father was the last official manager, and he lived in a small flat in the building between 1969-87. One of Peter’s most lasting memories of living in the baths was the penniless old men who visited Laurie Grove: “They came to the slipper baths in order to die with dignity. Destitute men who died washed and clean-shaven, and as my father always said ‘that were taken away as naked as the next man’ without embarrassment of being found wrapped in rags.”

The ‘slipper’ baths were so called because of the Victorian sense of modesty in draping bath-towels over the bath to conceal their bodies and by doing so making the bath look like a huge slipper. In 1962 there were 60 slipper baths still in operation and you could have a bath towel included for thruppence (3 d). The vast numbers of towels were washed and dried on huge racks that built on a pull out roller system at the rear of the main bath.

No surprise then that the building is said to be haunted. Peter told us that during the eighteen years that his father managed the baths numerous members of the public – even several police officers – witnessed strange phenomena. Almost always at night, these included lights coming on suddenly, doors opening or slamming for no reason. The said ‘poltergeist’ was affectionately known as ‘Charlie’ because he was given to whistling the tune ‘Charleston.’ Three members of staff left because of Charlie’s antics, two without giving notice.

Today, we share the building with the fine art students. The floor of the main swimming bath is divided into a grid of studios in which young artists work. The main bath when boarded was transformed into one of south-east London’s finest dance halls with a capacity for 800 dancers and also a venue for professional wrestling and boxing and an indoor bowling green.

The baths was also a female public sphere but not just for washing clothes. Attendances at the wrestling matches were largely working-class women. We have received several accounts of the bawdy fun had sometimes at the expense of male wrestlers in the ring.

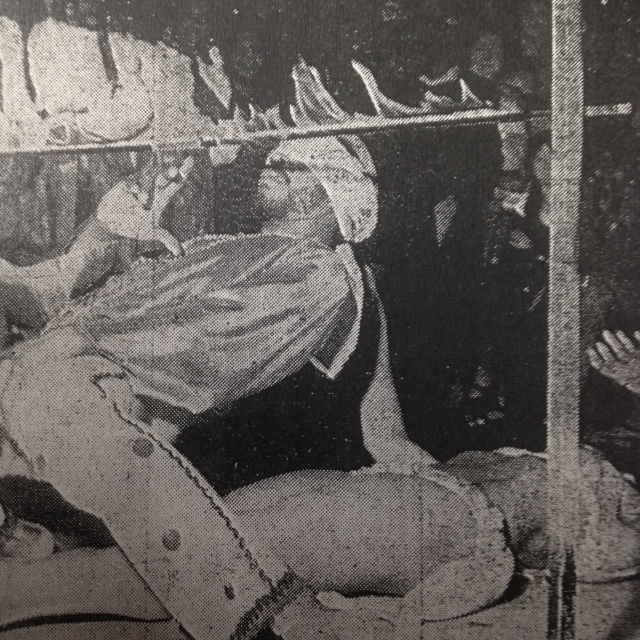

‘Limbo Dancing at Laurie Grove Baths’

from Lewisham Borough News 11th march, 1971

In 1954 Deptford Borough offered Laurie Grove to the Anglo-Caribbean Club as a meeting place and for events. George Brown, the organisation’s leading figure, pioneered the struggle for equal rights and opposition to racism. In 1961 the baths offered the venue for the Miss Brockley contest, a black beauty pageant that was won by student nurse, Yvonne Rosario. Some 500 people attended the event and partygoers converged on Laurie Grove from all corners of London. In a time when many of the pubs in South East London overtly excluded black people, the meetings and dances that were held in the baths were at the forefront of integration and breaking the colour bar.

In March 1971 limbo dancers Joyce Hutchinson and Kevin Livingston were flown in from Trinidad to perform at a dance held in Laurie Grove. Two bands performed for the dancers and Lewisham Borough News reported: The baths were filled with almost equal proportions of Lewisham’s coloured and white community.”

Much of the research work conducted at CUCR is in tune with the historical traces of gender, race and class within city life. It’s fitting that artist Wayne Binitie has been commissioned to make work that will focus on water, history and culture today. This project being developed in dialogue with visiting Professor Sophie Watson from the Open University in the coming months.

Images courtesy of Lewisham Local History and Archives

Les Back is Professor of Sociology at Goldsmiths College, University of London. L.Back@gold.ac.uk

5 thoughts on “An Urban Sociology of Water by Les Back”